Tag: Lee Friedlander

-

AMERICANSUBURB X: THEORY: "Lee Friedlander – Just Look At It" (2005)

Lee Friedlander: “Just Look At It” (2005) By Rod Slemmons Lee Friedlander was born in the logging mill town of Aberdeen, Washington in 1934. He began photographing in 1948 because of a “fascination with the equipment,” in his words. His first paid job was a Christmas card photograph of a dog for a local madam…

-

Dressing Up: Fashion Week NYC with Lee Friedlander | PDN Photo of the Day

Link: In 2006, Lee Friedlander was hired by New York Times Magazine Director of Photography Kathy Ryan to photograph backstage at the Marc Jacobs, Donna Karan, Calvin Klein, Zac Posen, Oscar de la Renta and Proenza Schouler shows

-

B: Another dusty old gem

Another dusty old gem My old teacher Rich Rollins recently sent me this chat between JP Caponigro and Lee Friedlander, originally xeroxed from a 2002 issue of C… Link: http://blakeandrews.blogspot.com/2019/05/another-dusty-old-gem.html My old teacher Rich Rollins recently sent me this chat between JP Caponigro and Lee Friedlander, originally xeroxed from a 2002 issue of Camera Arts…

-

B: Street Resurfacing Project

Street Resurfacing Project John Sypal recently sent me a photocopy of this old interview with Garry Winogrand, conducted by Charles Hagen. It was originally published… Link: http://blakeandrews.blogspot.com/2019/01/street-resurfacing-project.html John Sypal recently sent me a photocopy of this old interview with Garry Winogrand, conducted by Charles Hagen. It was originally published in Afterimage in December 1977, just…

-

Lee Friedlander’s Intimate Portraits of His Wife, Through Sixty Years of Marriage | The New Yorker

Lee Friedlander’s Intimate Portraits of His Wife, Through Sixty Years of Marriage Friedlander’s style of photography is usually cool, winking, and gamesman-like, but his pictures of his wife thrum with gentle affection. via The New Yorker: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/photo-booth/lee-friedlanders-intimate-portraits-of-his-wife-through-sixty-years-of-marriage Lee Friedlander once slyly assessed his promiscuous eye by saying, “I tend to photograph the things that get…

-

Viewing the World Through Lee Friedlander’s Fences | The New Yorker

Viewing the World Through Lee Friedlander’s Chain-Link Fences The photographer’s new collection bends a ubiquitous, mass-produced object to frame a portrait of American culture. via The New Yorker: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/photo-booth/viewing-the-world-through-lee-friedlanders-fences Like much of Lee Friedlander’s work, the ninety-seven photographs in his new collection, “Chain Link,” explore broad themes—sex, family, religion, race, nature—with striking wit. Friedlander has…

-

The Photographer Who Saw America’s Monuments Hiding in Plain Sight – The New York Times

The Photographer Who Saw America’s Monuments Hiding in Plain Sight Lee Friedlander provided an early study of our national fascination with statuary. Link: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/11/magazine/the-photographer-who-saw-americas-monuments-hiding-in-plain-sight.html?partner=rss&emc=rss Lee Friedlander’s “The American Monument” was first published in 1976. That’s “monument” singular, though one of the many singular things about Friedlander is that he’s nothing if not a pluralist. Whitman-like,…

-

How Lee Friedlander Edits His Photo Books | PDNPulse

How Lee Friedlander Edits His Photo Books | PDNPulse Lee Friedlander has published 50 books in his career to date. And he’s not stopping. The legendary photographer (born 1933) and his grandson, Giancarlo T. Roma, recently revived Haywire Press, the self-publishing company Friedlander established in the 197 via PDNPulse: https://pdnpulse.pdnonline.com/2017/07/lee-friedlander-edits-photo-books.html Friedlander said he typically Xeroxes…

-

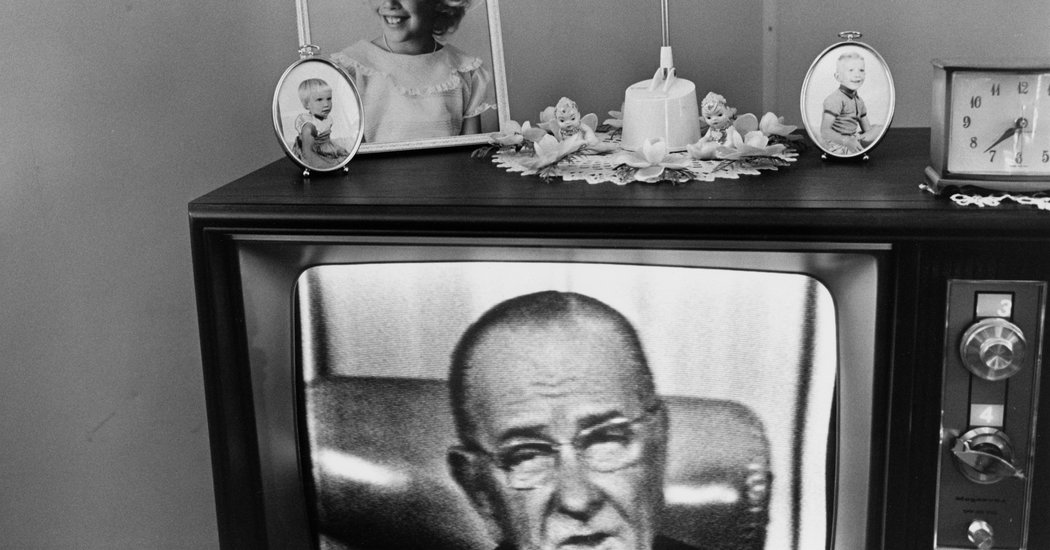

Lee Friedlander’s Photos of 1960s T.V. Sets – The New York Times

Lee Friedlander’s Photos of 1960s T.V. Sets Lee Friedlander’s series “The Little Screens” was an early artistic attempt to document television’s nascent dominance of America. via Lens Blog: https://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2017/07/03/lee-friedlanders-photos-of-1960s-t-v-sets/?module=BlogPost-Title&version=Blog%20Main&contentCollection=Multimedia&action=Click&pgtype=Blogs®ion=Body As such, it is disconcerting to see the installation of Lee Friedlander’s prescient “The Little Screens” on the wall at Pier 24 in San Francisco, as…

-

Lee Friedlander’s Overlooked Civil Rights Photos – The New York Times

Lee Friedlander’s Overlooked Civil Rights Photos The photographs in Lee Friedlander’s book “Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom” are of a subject not usually associated with him: the civil rights movement. Among his earliest and least typical images — the photographer was only 22 when he made them — they document a historic, if lesser known, event…

-

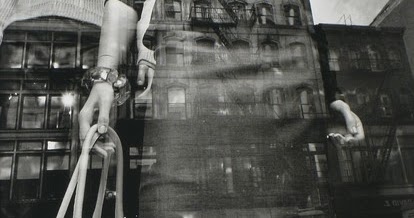

Lee Jumps The Shark

Lee Jumps The Shark For fans of Lee Friedlander, his recent book Mannequin offers good news and bad. The good news is that the master has returned to the 35 m… Link: http://blakeandrews.blogspot.com/2012/08/lee-jumps-shark.html For fans of Lee Friedlander, his recent book Mannequin offers good news and bad. The good news is that the master has…

-

LEE FRIEDLANDER: "Out of the Cool" (1991)

‘Like a One Eyed Cat’, Lee Friedlander – Out of the Cool Haverstraw, New York, 1966 Friedlander is a photographer, never forget. Although a major photographic artist, he is not an ‘artist utilising photography.’ He uses the camera, that unthinking machine, to transcribe his visual perceptions of the world. via AMERICAN SUBURB X: http://www.americansuburbx.com/2011/07/lee-friedlander-out-of-cool-1991.html?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed:+Americansuburb+(AMERICANSUBURBX) The…

-

PDNPulse: Gallery and Library Buy Make Yale Largest Holder of Lee Friedlander’s Work

Also included in the acquisition are 40,000 rolls of film spanning Friedlander’s work since the mid-1950s. Link: PDNPulse: Gallery and Library Buy Make Yale Largest Holder of Lee Friedlander’s Work

-

5B4: Lee Friedlander Photographs Frederick Law Olmsted Landscapes

This project in particular is interesting because it came at a time when Lee was experimenting with different camera formats and frame ratios. Within the span of the 89 images in Frederick Law Olmsted Landscapes he shifts from his Leica, to a Noblex pivoting lens panoramic camera, to his Hasselblad Superwide, and the results are…

-

Blush, Sweat and Tears

NYT Magazine: Since the 70’s, Lee Friedlander has been intermittently documenting Americans at work: employees in a Cleveland steel mill, telemarketers in an Omaha calling center, M.I.T. technicians staring into their computer monitors. A few weeks ago, Friedlander encountered some very different production values when he turned his eye to the glamour factory otherwise known…