These 11 photos were all shot in the town of Ironwood, Michigan on the hottest day of 2012 — around 100° Fahrenheit (38° C).

Category: Portfolios & Galleries

-

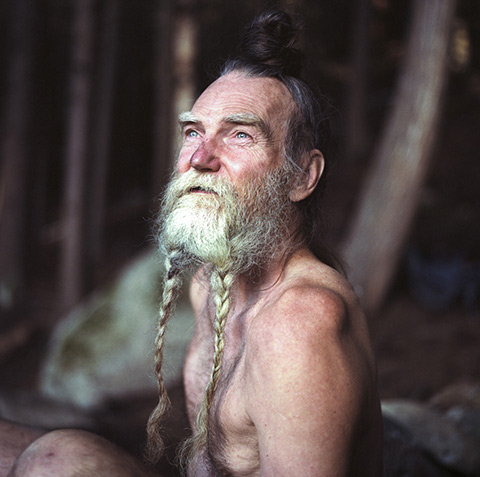

Photos Explore ‘Back to the Land’ Movement in Canada

Photos Explore ‘Back to the Land’ Movement in Canada

Photographer Kari Medig grew up in a cabin in northern British Columbia. He is drawn to acts of photography that involve a physical element. The tougher and more remote the environment, the happier he is. His series Back to the Land is an ongoing project that examines the intersection between humans and nature.

via Feature Shoot: https://www.featureshoot.com/2013/06/photos-explore-back-to-the-land-movement-in-canada/

Photographer Kari Medig grew up in a cabin in northern British Columbia. He is drawn to acts of photography that involve a physical element. The tougher and more remote the environment, the happier he is. His series Back to the Land is an ongoing project that examines the intersection between humans and nature

-

Happy Father’s Day: Portraits from America’s Purity Balls

LightBox | Time

Read the latest stories about LightBox on Time

via Time: https://time.com/section/lightbox/

When the Swedish photographer David Magnusson created the pictures for his series Purity — now on view at the Malmö Museer as part of his first solo show — he followed the same procedure every time. One hour with a large-format camera. Sixteen pictures taken; one used. In front of the lens, a father and his daughter(s).

-

Cuban Evolution: Photographs by Joakim Eskildsen

LightBox | Time

Read the latest stories about LightBox on Time

via Time: https://time.com/section/lightbox/

“I immediately fell in awe with the complexity of this country,” says Eskildsen. “The more you learn about the situation and how people are living, the more difficult it becomes to understand. It was like learning to view the world form a Cuban angle that kept surprising and inspiring me.”

-

Arles 2013: South Africa Viewpoints

The 2012/2013 France-South Africa Seasons project was set up to engage a dialogue between two peoples. It brings together artists who did not necessarily know much about each others’ work : six South African and six French photographers who met and joined forces in an adventure which began in South Africa in 2012.

-

When Buddhists Go Bad: Photographs by Adam Dean

LightBox | Time

Read the latest stories about LightBox on Time

via Time: https://time.com/section/lightbox/

The spectacle of faith makes for luminous photography. Buddhism, in particular, lends itself to the lens: those shaven heads and richly hued monastic robes; the swirls of incense; the pure expressions of devotees to a religion whose first precept is “do not kill.” But as photographer Adam Dean and I discovered when traveling through Burma and Thailand from May to June, Buddhism’s pacifist image is being challenged by a radical strain that marries spirituality with ethnic chauvinism

-

Looking Back To Move Forward: 13 Years Of Photographing Afghanistan

Looking Back To Move Forward: 13 Years Of Photographing Afghanistan

Saying goodbye to something you’ve known for a decade can be a landmine of emotion — even if that thing is a war.

On his most recent trip to Afghanistan, NPR staff photographer David Gilkey shot this personal iPhone photo essay in his downtime

-

Gay Pride and Same-Sex Marriage Around the World

A Timely Victory

via The New Yorker: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/photo-booth/a-timely-victory

Ladakh, nestled in the northernmost realms of India between the Kunlun and Himalaya mountain ranges, is one of the last remaining strongholds of Buddhism in South Asia.

-

A Period of Transition in South Africa

“‘Second Transition’ is the term that came to mind when I was photographing in Brits, Ga-Rankuwa, Marikana and Rustenburg,” says Sekgala. “Second Transition” describes a new phase of negotiations under Apartheid,” he adds, referencing the farms located between Brits and Rustenburg, an area of about 40 miles, that were assimilated and eventually became the independent state of Bophuthatswana after the introduction of the Natives Land Act in 1913.

-

Steichen’s Family of Man Restored: New Life for a Photographic Touchstone

LightBox | Time

Read the latest stories about LightBox on Time

via Time: https://time.com/section/lightbox/

In 1955, a decade into the Cold War, the Museum of Modern Art in New York opened its doors to a monumental photography exhibition, an aesthetic manifesto visualizing ideas of peace and “the essential oneness of mankind.” Edward Steichen, then director of the MoMA photography department, curated 503 photographs — from a pool of two million — by 273 artists from 68 countries with the at-once simple and grand goal of definitively “explaining man to man.”

-

Photo Essay: Chasing Meth in Laurel County, Kentucky

Photo Essay: Chasing Meth in Laurel County, Kentucky

Stacy Krantiz’s intimate look at methamphetamine addicts and the cops trying to to nab them.

via Mother Jones: https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2013/08/photoessay-meth-laurel-county-kentucky-kranitz/

The first call we went on was in an abandoned trailer with no running water or electricity. The walls were covered with cryptic texts and morbid poems. Jason arrested three repeat offenders who were squatting there, and they were very nice about the whole bust. They would joke with Jason and talk about mutual friends. It was much more casual than I had expected

-

Daniel Zvereff: Unecha

As I walk around Unecha, I wonder what it is about this place that feels so nostalgic to me. I can’t help but think about all the events that took place in order for me to be here as a stranger: the Russian revolution and World War II, which sent my father’s side of the family first to China and then, finally, California, and my mother’s chance meeting with my father. I don’t feel like I am of this place, but I also don’t feel completely severed from it.

-

Moises Saman in Cairo

Moises Saman in Cairo

via The New Yorker: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/photo-booth/moises-saman-in-cairo

“In the two years since I moved here, every milestone of the revolution has been marred by an outburst of street violence,” he says. “However, the events of the past week are unprecedented: rocks have been replaced by sniper bullets, city mosques transformed into front line field hospitals, and isolated street clashes superseded by systematized killings.”